Vintage Comix I

by Jay Kinney

I first became involved with what were then called "underground comix" in 1968, when I drew my first published strip for Bijou Funnies, edited by Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson. I was 18 at the time, and my early work was, well, early. By the time I did the stories displayed here and on the next page, I had advanced considerably. Much of my work over the years was done in collaboration with Ned Sonntag and Paul Mavrides, but the work below was mine alone, with one exception. Just as the underground press evolved into the alternative press in the course of the '70s, underground comix evolved into alternative comics. In the early '80s, I shifted away from art to concentrate on writing and editing, first as editor of CoEvolution Quarterly, and then as publisher and editor in chief of Gnosis Magazine. In the last few years, I've again ventured into cartooning. I am interested in pursuing this further. Publishers, take note!

Romance Comic satires

Forty years ago, DC and Marvel were still cranking out "romance comics" such as Young Love. Bill Griffith (of "Zippy the Pinhead" fame) and I had the bright idea to create an "adults only" satire of the genre, Young Lust. It became one of the top three best-selling underground comix, along with Zap Comics and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. These were two of my best strips for the comic: my memoirs of Fifth Grade and a satire of the Maoist Cultural Revolution. [If you are under-18, please grow up before you read these. 'Nuff said.]

Dystopian Visions

Bear in mind that these neo-classical "science fiction" strips were done in 1974-75, when the future looked pretty grim to me. "Dry Ice" was an exercise in projecting then present trends into the future. "Midnight" was an product of the last gasp of my countercultural dreams: going back to the land to get away from political madness. I regarded these strips as silent movies on paper.

-

-

-

-

- Dry Ice

First published in

Short Order

No.2, 1974.

4 pages, black and white.

Available as limited edition

8.5" x 11" signed prints.

Contact Artist.

Poetry in Panels

The third (and last) in my series of silent strips, "The Garden," was commissioned by Stewart Brand for his new magazine, CoEvolution Quarterly, in 1975. Several years later, I returned to the dialog-free format, merging poetry and art this time, in collaboration with friend and poet Adam Cornford, with "Black Cat City," a dark political dreamscape.

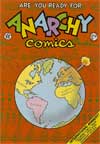

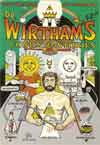

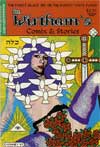

Comic Covers

Most full color covers (as well as the color strip at the top of the page) were painstakingly hand-separated, using acetate and Zipatone screens. (This is now considered archaic technology, only one step removed from hot lead typesetting Linotype machines.) The cover of Occult Laff-Parade (1973) is an example of this process. The cover for Anarchy Comics No. 1 (1978) was partly hand-separated and partly the product of extensive darkroom negative manipulation, (also a rapidly disappearing skill). The cover for Dr. Wirtham's Comix & Stories No. 7 (1982) — a tongue-in-cheek portrayal of the creative process as an alchemical operation — was another hand-separated work-out. The cover for Dr. Wirtham's Comix & Stories No. 9 (1987) — a meditation on the sacred prostitute archetype, facilitated by a rough scan of some old smut — was an exercise in bit-mapped art and a mixture of hand and computer color separation.